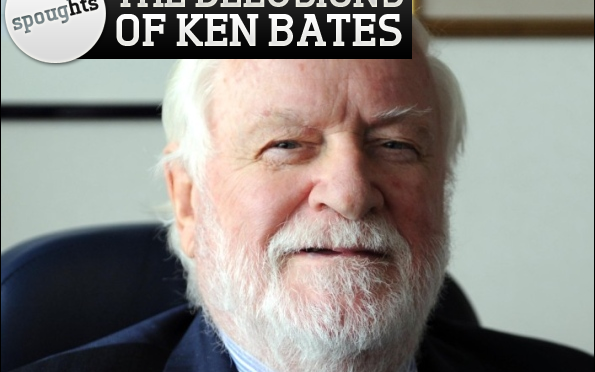

Ken Bates is completely sure that what he does at Elland Road is correct. As much as the various outlets that criticize the running of the club disagree with what occurs, that one fact can stand above all others as an undeniable truth. The man in charge is completely, entirely, devoutly convinced that the Ken Bates method for running Leeds United is right. Not only this, it is the only way. The only way that Leeds United can have a future, Ken Bates feels, is through him.

A dictator is defined as “a ruler with total power over a country, typically one who has obtained power by force”. Many people would suggest that equating the chairman of a football team with those who cause strife around the globe as ridiculous. I would probably have agreed a mere seventy-two hours ago. This week, however, was the week in which the extensive nature of Ken Bates’s delusions came to the fore. He, dictating down to one of the various lackeys who crop up in statements that come out of the club, decided to ban the board of the Leeds United Supporter’s Trust (LUST). Clearly, judging by Ken Bates’ weekly interview that occurred a few days ago, this is in response to a group he knows little and cares little about. It must, therefore, have been as part of a giant cull of fans, because otherwise the event would not have occurred.

In doing this, Ken Bates has managed to galvanize the support base. Ideally, he would have hoped it had brought about a fan base united behind himself. He’d finally proven to the world that these were merely ‘morons’ and ‘sickpots’. Even if he hadn’t, at least these people who opposed him would no longer be an intolerable nuisance in the ground he does not own.

There are several fundamental flaws with this concept however. The first stems from the facts the majority of Leeds fans have become well acquainted with. Ken Bates, in his budgeting of Leeds United, spends at most 42% on the playing side of the team. We’ve covered this thoroughly already, but the fact is worth repeating. Football is primarily a game of dreams, a game in which fans should enter a season with hope and dreams about what may have unfolded by the end of the year. Yet Leeds have a set of fans well-adjusted to the notions of a summer of discontent. Last summer alone, Leeds lost several key first team players. It was clear the season was not going to be a positive one. This runs opposed to the very nature of football. Simon Kuper wrote about the almost permanently solvent nature of football clubs in The Blizzard, arguing that football clubs will always exist in one form or another, given the significant demand for them. Leeds fans do not ask for ridiculous debts to be run up, but they do ask for at least some risk, as without this, reward cannot come.

Secondly, as much as Ken Bates seems unwilling to accept this fact, there are laws governing the island on which his football team resides. Aside from the potentially repeated violations of the Data Protection Act in his weekly address, Ken seems convinced that denying LUST an outlet in the stadium is to deny them any outlet at all. Sadly for Kenneth, the ‘wishy-washy BBC watching liberals’ in charge incorporated the European Convention into UK law in 1998. This guarantees freedom of speech under the Human Rights Act. So, where Ken publishes only the positive through his various outlets, the various publications that people turn to for Leeds United news will continue to report the realities of the situation at Elland Road. This one incident alone has swelled the ranks of the Supporter’s Trust by a ‘mere’ thousand members. This is not Noel Lloyd. Ken is not the dictator of a secluded paradise. The outcry can, and may well lay siege to Bates’ regime at Elland Road.

Finally, Ken doesn’t seem to understand the movements football governance is taking. The Supporter’s Trust movement is backed by no less than the current Con-Dem Coalition, ideologically most likely to support anything that leaves business alone. For them to show this sort of opposition to the politics of football shows how far in the wrong direction it has travelled. English football is finally making moves towards the German model of ownership. Should Ken not rectify his relationship with the Supporter’s Trust, he may soon find himself permanently attached to a very hostile 51% co-owner.

Ken should therefore genuinely rethink his actions at Elland Road. Whether it is merely the output of his media outlets, or the actions he takes with regards to the fans, or if he does a proper rethink of the club’s policies, now is the time, ahead of next season, with mild positivity in the air, to really take advantage. Football is, by its very nature, for the fans. The fans are beginning to seriously demand change at Leeds United, and as LUST say, Ken Bates can easily be part of that. Alternatively, he can become an eternally decried figure in the annals of the club.

Amitai Winehouse is followable on Twitter @awinehouse1. Read his article, ‘The Gwynterview’ in the latest issue of The Square Ball, available now.